Clementine Hunter: An American Painter

Christopher Clother

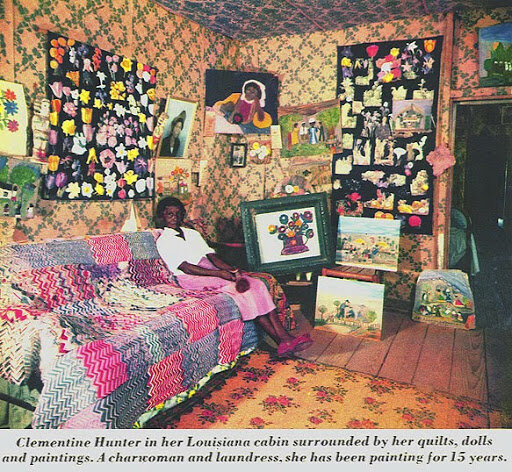

Clementine Hunter

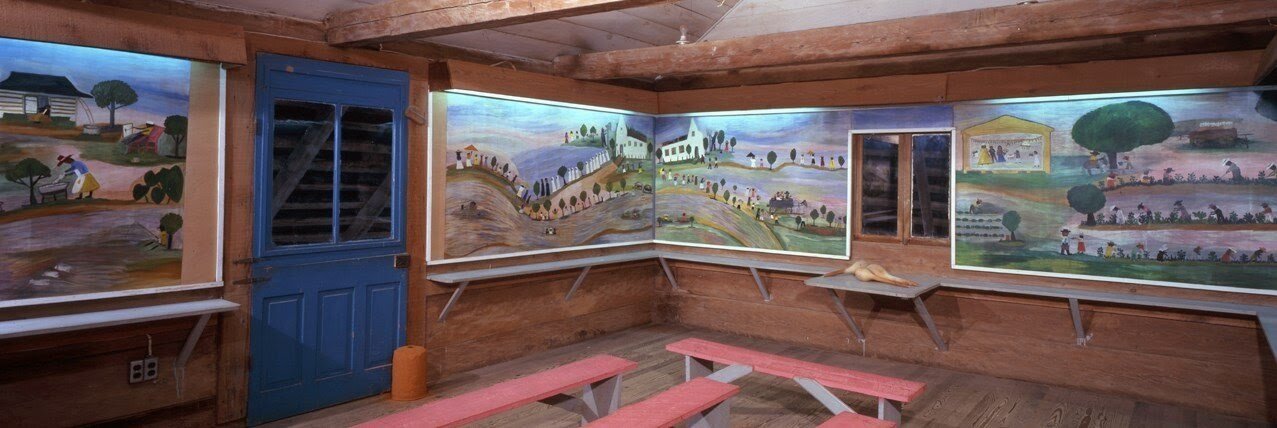

In rural central Louisiana on the banks of the Cane River sits Melrose Plantation. With roots that reach well beyond the beginnings of the European colonization of the region, Melrose has supported Native American tribes, early white and Creole farming communities, endured the violence of the Civil War, and later, acted as an artist's retreat. Early in its development by Westerners, an enigmatic structure was erected on the property, called the African House, that now stands as an unexpected symbol of cultural confluence and the validation of individual significance. Today, the upper floor of the building houses The African House Murals, the largest and most celebrated artworks of Clementine Hunter, who lived for the majority of her life on Melrose Plantation, and whose legacy of humble self-determination stands in direct relationship to that of the founders of the place we now call Melrose. This article will explore the work of Clementine Hunter by accounting for her life story, the history of her home, and assess the unique and definitive qualities of her painting.

Clementine Hunter is one of the South’s most celebrated folk artists, an untrained painter who began her career only after she’d reached her fifties. Unable to read or write, she shared her memories of life working in rural Louisiana by producing vibrant pictures. The paintings of Clementine Hunter depict an uncomplicated, organized world full of bright and lively individuals engaging in community activities. There is abundant foliage and flowers, often arranged along stacked horizon lines. The people, too, are put in careful order: walking in processions, dancing in couplets, gathered around a wash tub, equidistant throughout a cotton field. They’re like dolls arranged within a miniature land by a child expressing independent agency. In fact, her work is often considered childlike and innocent; her heavy handed and immediate depictions thought to be little more than naïve nostalgia. Though her paintings have an obvious simplicity and an inherent optimism, when considering the social milieu in which she worked it becomes clear that the underlying impulse of her work is rather an act of resistance. The conditions of her upbringing, the lack of opportunities afforded to her, and even the circumstances that resulted in the opportunity for her to paint are all derivative of a hateful social order that she worked to fight against.

Baptism, detail of African House Murals, 1955, oil on wood

Clementine Hunter was born near Cloutierville, Louisiana around Christmas of 1886. She was the first of seven children, and her parents, Marie Antoinette Adams and Janvier (John) Reuben were French-speaking farmhands at the Hidden Hill Plantation, supposedly the site that inspired Uncle Tom’s Cabin. They were French Creole: of African, Irish, and French descent, and Clementine’s grandmothers on both sides had Native American ancestry. Slavery was fresh in the minds of everyone in the South, and conditions were wretchedly poor for farm laborers. Shortly after Clementine’s birth, her family began seeking work elsewhere, in hopes of getting away from the degraded conditions at Hidden Hill.

Amidst the moving around, Clementine had a brief experience of the late 19th century education system in the South. At five years old, she attended school for the first time, and found a segregated, cruel environment that, though promising the virtues of literacy, would insist on her complacency in a social structure that derided her humanity. A price she was unwilling to pay, she fled the school most days to join her father working in the cotton fields, and by the end of that first school year, her parents decided to keep her with them. Clementine never learned to read or write, but exchanged that opportunity to be in community with the people she loved. Even though the labor was back-breaking, she described her experiences in the cotton fields or harvesting pecans as joyful and happy.

At the age of fifteen, Clementine moved with her family to the place she would live in and around for the rest of her life, the place where she would find love, raise her children, and be supported in her passion for painting: Melrose Plantation. Likely drawn by the promise of tolerable working conditions, her parents went into the employ of John and Cammie Henry shortly after the turn of the century. Clementine joined them, again working the cotton fields and harvesting pecans.

When Clementine was in her late teens, she became involved with an extraordinary man fifteen years her senior with unparalleled aptitude for mechanics. Charlie Dupree (“Cuckoo Charlie”) was said to have built a piano without having seen the instrument in person, and actually constructed a functional steam engine with only a description to guide his effort. Cuckoo Charlie was father to Clementine’s first two children, though, by her own admission, she was “just keepin’ company” with the man. Considering the apparent willful creativity expressed by both these individuals, one can imagine the nature of their attraction. Perhaps in Cuckoo Charlie, Clementine found someone she could truly relate to and admire.

Washday , 1950s, oil on board

Charlie Dupree died in 1914, leaving Clementine to care for the children while keeping a full-time work schedule. For ten years, she managed with the support of her family and the community of workers at Melrose, and, in 1924, she married a woodchopper at the plantation named Emanuel Hunter. She described him in amiable and practical terms, as though he were a stable choice and a means to predictable care for her children. It is important to note that, at this point, Clementine spoke only Creole French, effectively limiting her social circle to her immediate community. The broader American context, perpetuated by radio and print media, was inaccessible to her, and she only ascertained snippets of the world outside rural Louisiana through the filter of that immediate community. This changed when she married Emanuel, who taught her how to speak, in her words, “American.” With him, she bore five more children, two of which were stillborn, though she still counted them when taking pride in comparing herself to her mother, who also had seven children. Both her parents had died before she was 21.

Even with the tremendous demands of motherhood, Clementine was a determined and diligent worker, supposedly picking quantities of cotton right up until going into labor, and then returning to work only a few days after. While this seeming tenacity may translate as remarkable strength, and certainly it does, it is also the by-product of a culture that regards with indifference the needs of a servant class. It is inhumane to insist a mother late in pregnancy to engage in back-breaking field work, or to ask a new mother to return to such physical demands so soon after childbirth. Additionally, Clementine was expected to work without childcare for her newborns, and adapted by tucking her babies in the shade of a tree at the end of the cotton rows. When she had worked to the row’s end, she would attend to her child before setting off to work the next row. She endured these circumstances, until, having endeared herself to the mistress of the plantation, “Miss Cammie” Hunter, she began working as a maid in the Big House in the late 1920’s.

Working in the home, Clementine began to find outlets for her self-expression, and also received validation and encouragement. She was a skilled seamstress, and created beautiful quilts, lace curtains, and dolls for the white children of the plantation. She was an exceptional cook, earning renown amongst the guests of the Big House for her interpretation of French Creole classics. By the 1930s, Melrose Plantation had become a thriving retreat for creative types, invited by Miss Cammie to receive room and board and to work in peace, and many took note of Hunter’s affable demeanor and expressive skill set. Melrose Plantation hosted such names as William Faulkner, Rachel Field, Ada Jack Carver, Roark Bradford, and Alberta Kinsey; but it was one guest in particular who encouraged and championed the skill of Hunter. In 1938, François Mignon commenced his three decade relationship with Melrose Plantation, and established himself as influential in Clementine’s artistic career.

Window Shade, oil on board, 1950s

As Melrose had become home to various writers and painters, it began to fall to Hunter to clean studio spaces, providing her with regular encounters with painting materials. It was around 1940 that, one evening, she approached Francois Mignon for the first time to inquire about putting to use the half-empty tubes of paint discarded by other guests. Mignon, already friendly and familiar with Hunter, knew she was gifted by virtue of her many quilts and dolls, and provided her with an old window shade to work on. She happily took it and returned to his door at 5:00 am the following day with a “marked picture” to show him. Floored by her unique vision, Mignon took to providing her with a continual flow of supplies and helped to start her off on her prolific painting career.

Clementine Hunter

Mignon suspected that the painting she initially brought to him was not her first, and believed that she had been helping herself to discarded paint tubes and other such supplies for some time. When Hunter approached Mignon, it was rather a confession with the hope of receiving validation for how she’d chosen to use her time. Hunter’s life was seemingly used up: since her adolescence, the workday lasted from sunrise to sunset, and, by 1940, she had a full complement of children and grandchildren needing support before and after work. She was regularly given washing and ironing to take home with her, and, in the 1940s, her husband, Emanuel, had become ill and was left bedridden. Such demands were status quo, but the ceaseless toil Hunter endured did not relieve her of her passion for creative expression. Painting was understood as a leisurely pastime of the white ruling class, and for Hunter to come out as interested in painting, or to confess that she had already been painting, could have invited scorn from her employer and her family.

Providentially, Mignon was supportive, which was perhaps an encouragement for her to introduce her passion to the rest of her family and friends. Not that the accolades of the white academic in the Big House could in any way lighten her load. Her open pursuit of painting was confined to late nights, often by the bedside of her ailing husband. Emanuel expressed his anxiety for her well-being due to lack of sleep, but she assured him that if she didn’t get her paintings out of her head, she’d “sure go crazy.” In fact, Hunter was not one to lament her situation, though she was certainly capable of imagining an alternative version of life. Living for fifty years as oppressed and disenfranchised taught her to quietly make do with what little she could cobble together, and to understand that at no point was it going to be easy. Her example speaks volumes of the compulsion of the creative spirit that can’t be extinguished, no matter the social adversity.

Harvesting Gourds near the African House and Wash Day Near Ghana House, Melrose Plantation,1959, oil on board, 73” x 66.5”

Once she had begun, Clementine could not stop producing painting after painting. Though hardships mounted as Emanuel’s health diminished, Clementine seemed to be driven all the more to fill any surfaces she could get with the memories of her life. She painted on old window screens, bits of cardboard, boxes disassembled and turned inside out, vases, glasses, and, when Mignon could get them for her, proper canvases or panels. It’s noted that much of her earlier work has washy backgrounds, as though she had used watercolor to suggest the sky and rolling hills. This effect was rather born of want—having so little paint, she diluted what colors she had with turpentine to adequately cover the surface. The support she received from Mignon eventually led to her making the acquaintance of another white scholar, James Register, who was so determined to see Hunter’s work reach a broader audience that he began sending her money and art supplies monthly, and even secured a grant to fund her work.

Emanuel Hunter died in 1944, after which Clementine’s productivity seemed to further accelerate. Mignon would walk the mile from the Big House on Melrose Plantation to Hunter’s modest cabin, delivering canvases and paints, lingering to chat, then return a few days later to receive what stack of paintings she’d produced. She gave them freely, always uncomfortable with the idea of selling her work (when absolutely pressed, she might let one go for 25 cents), and was happy for Mignon to collect them, distributing some to various interested parties. With the help of Mignon and James Register, Hunter had her first art shows in 1945, and her work was installed in the local drug store where they could be bought for a dollar a piece.

So, what of these “marked pictures” that would drive Clementine crazy should she fail to get them out? How is one to understand the nature of such a fervor? Hunter painted the same subject matter over and over again: scenes of labor in the fields, attending church for baptisms, funerals, and weddings, brawls outside the local honkey tonk, doing the washing and the cooking. Some estimate she produced beyond 5,000 paintings during her late-life career, and though she took the occasional detour with her choice of subject, her work consistently returned to depictions rooted in memory. She described her process as follows: “I just get it in my mind and I just go ahead and paint but I can’t look at nothing and paint. No trees, no nothing. I just make my own tree in my mind, that’s the way I paint.” Painting from life and painting from memory are often held as a dichotomy, and painting from life has generally been considered a superior practice by traditionally Western artists. The effort found an early expression in Greco-Roman culture, and existed as a motive force throughout the European Renaissance on up to recent modernity. It stands as a corollary to the ideology of the scientific method, where objective knowledge is valued over subjective experience. To paint from life suggests an effort to explore the world as it is for everyone, somehow apart from the unique phenomena of the artist’s individuality, and while many have found value in such an approach, reveling in the myth of an objective human narrative can negate the diversity of human experience. In fact, to create work that has its source in memory is something fundamentally (even, uniquely) human, and working to isolate ourselves from this incontrovertible, inescapable condition of communicating our experiences to each other is nothing less than self-deception.

Funeral Procession, oil on board, 11” x 18.25

Hunter’s paintings revel in memory. In considering the source material for her images, there is little to recognize beyond her personal recollections of life lived and imagined. Having been illiterate, essentially unschooled, and with minimal exposure to media (books, magazines, television, etc), her work can only be derivative of her life alone. While artworks rich with cultural associations can be psychologically revealing of their creators, locating the heart of the artist in such work can be challenging, and the work itself can wind up feeling distant or even insincere. By making her work singly concerned with the transference of memory, Hunter’s images achieve a moving sincerity that imbues her images with complex meaning, not dissimilar from listening to Hunter tell her story orally.

Clementine Hunter, “50¢ to Look”

In telling our story, whether through conversation, writing, painting, etc., we are afforded an opportunity to exert agency over our identity and the world we grew up in. We can focus on certain parts, disregard others, exaggerate what we consider important, so that in relating our narrative we are able to bring a certain justice to our experiences. Consider the two paintings, Funeral Procession and Saturday Night at the Honkey Tonk, which feature scenes and themes Hunter explored frequently in her art. These are undated works, foreseeably from the middle of her career (Hunter didn’t sign her earliest work, and dated her work inconsistently. Mignon instructed her in how to write her initials on her paintings, which she began doing in the mid 1940s. She began by writing her initials conventionally, and then started to flip her “C.” Later, she chose to overlap the “C” and the “H”—art historians can now gauge the date of her works by noting how she wrote her initials). Both depict something of a community gathering, where the event at hand has brought together many people from throughout the county. In Funeral Procession, we see the people arranged in single file, descending from the church which sits in the top right corner of the composition, at sky level, its steeple reaching up and out of the picture plane (right up into heaven). Two men carry the casket and two men have dug the grave, which acts as a mirror to the church directly above, the grave reaching off the lower edge of the plane. The image is orderly and composed, nothing overlaps, and everything important is rendered visible. The inherent grief associated with death is hardly apparent as those in attendance are blank-faced and wide-eyed, like paper dolls that could be placed into an altogether different scene without issue. In fact, considering the heaviness associated with funerals, this painting is surprisingly bright and uplifting. Hunter took care to depict the lovely bouquets and matching outfits of the women, the sky is blue, and the land an unexpected shade of salmon pink. By emphasizing the color and contriving a visually impossible order, Hunter has tamed the pain of death, making an otherwise challenging memory navigable.

Saturday Night at the Honkey Tonk functions in a similar manner. Here we see what would have been the winding down of the evening, everyone drunk and terrible violence ensuing—this painting could even be read as the precursor to Funeral Procession. The composition here is similarly schematic in arrangement, with figures positioned so none overlap and all action is fully visible. Though there is, again, nothing in the way of emotional expressivity, this image is heavy with the association between alcohol and violence. Blood spills conspicuously, the act of murder is frozen in time, and the bullet that has already shot down the women to the left is illogically seen flying from the barrel of the gun. This motif was painted again and again by Hunter, driving home the impact such trauma had on her as an onlooker (she’s said that, though she went to the honkey tonk, she was very disapproving of the violence that seemed to result). However, there is an enigmatic central figure dressed in yellow, knife, or club, to the head, a stream of blood coming from her face, and what appears to be a paintbrush in her hand. Where Funeral Procession restructures the communal grief of death as ordered and vibrant, Saturday Night at the Honky Tonk may be showing the transmutation of a very personal trauma, physical violence done to the artist, into a digestible fact. By painting and repainting the same scene, Hunter is continually giving form to unseen, personal experiences, and, in a sense, exorcises them from her being.

Saturday Night at the Honkey Tonk, oil on board, 16”x24

Clementine’s work continued to garner broad attention, her art was shown not just in Louisiana, but in surrounding states as well. Francois Mignon remained at Melrose, close to Hunter, and carried on his role connecting her to collectors, funding her supplies, and speaking on her behalf to interested institutions. 1955 was a big year for her, being the opening of her largest solo exhibition to date, and the year she undertook the African House Murals. The exhibition in question was hung at the Northwestern State University of Louisiana, and the museum was a strictly segregated space. Though Hunter was the star of the show, she wasn’t permitted to enter the building; however, the curators did sneak her in through a back door when no one was around so that she could see her work installed in the imposing space. One can only imagine the emotional upheaval from the cognitive dissonance of feeling accepted and celebrated by an institution that won’t allow you to cross their threshold.

Back at Melrose Plantation, Mignon had been overseeing the revitalization of one of the truly notable historical structures on the property: the African House. A modest, four-walled, two story building with an absolutely massive thatched roof with eaves that reach down and over the entire second story, this structure is thought to be an assimilation of multiple cultural expressions. The story of its conception is unclear, but it’s thought to have been the product of both African and Native American architectural ideas. In an American landscape dominated by recycled European architectural tropes, the African House stands anomalous, representing an often unconsidered aspect of Creolization: the confluence of African and Native American cultures. It’s lower floor has barred windows and some stories suggest that it was used to imprison delinquent slaves owned by the Metoyer family, the founding family of Melrose Plantation. Its upper floor was likely used for drying tobacco.

Look Magazine, 1953

The story of the Metoyer family, specifically their materfamilias, Marie Therese Coincoin, bears mentioning, due to its synchronous relationship to the life and work of Clementine Hunter. Marie Therese Coincoin was born a slave in 1742 to the household of the founder of Natchitoches (one of the oldest permanent settlements in Louisiana, named after the indigenous people of the region, which sits fifteen miles north of Melrose) when Louisiana was still a French colony. At the age of twenty-six, Coincoin met the merchant Claude Thomas Pierre Metoyer who was taken by her beauty and charisma. Metoyer leased her from her owner and they commenced a nineteen year relationship, bringing ten children into the world. All told, Metoyer was kind to Coincoin and worked alongside her and their children in the fields, accruing property and wealth through land grants from the French government. Over the years, as money allowed, Metoyer set about purchasing and freeing Coincoin and some of their children, and balked when local churches condemned his un-sanctimonious relationship. Their relationship came to an end, however, when Metoyer recognized he needed to produce a “legitimate” heir, and took a local widow for his wife.

He gave Marie Therese and their children a parcel of land and a meager monthly stipend, by which the ever industrious Coincoin established the foundation of a bustling community, Isle Brevelle, epitomizing the definition of Creolization: where new cultural expressions are brought about through contact between societies and relocated people. People of African, Native American, French, and Spanish descent grew crops together and served each other as artisans, shoemakers, woodworkers, and cooks. People in such communities were referred to as “Gens de Couleur Libre” (Free People of Color), and one of their objectives was to grow wealth for the purpose of purchasing freedom for friends and family yoked by slavery. In order to earn more income, Coincoin and her family bought slaves to work their land, essentially buying into a system in order to subvert it. Free People of Color would pick cotton right alongside those enslaved to do the work, fostering community ties despite the sordid nature of the work relationship. Coincoin’s oldest son commissioned a church to be built for the community, believed to be America’s first built by and for “Gens de Couleur Libre,” and it’s said that white attendants of the church were restricted to the back of the building.

Melrose Plantation, Big House, African House, detail of African House Mural, 1955, oil on wood

Marie Therese’s son Louis Metoyer established what we today refer to as Melrose Plantation, and between 1810 and 1815, he oversaw the construction of several humble buildings on the site, one being the African House. He and his family resided in the Yucca House, another of the original buildings that still stands today, and is featured in numerous paintings and quilts of Clementine Hunter.

Clementine Hunter

During the 19th century, the Melrose Plantation eventually fell from the hands of the Metoyer family, though their descendants still live in the region to this day. The property changed hands through the years, the Civil War was fought on the doorstep of Melrose’s Big House, and the land was eventually acquired by the Henry family in 1881. Clementine Hunter and her family came to work for the Henry’s some twenty years later. Perhaps it’s fair to say that the blood and sweat of Coincoin and the Metoyer family laid the psychic foundations for self assertion involved in Hunter’s decision to create. Erecting a building that speaks to the ancestry of slave culture would certainly have provided some sort of subconscious validation to Hunter, helping her believe that her story was worth telling. Hunter has even paid homage to Marie Therese Coincoin and her partner, Thomas Metoyer, in the African House Murals; depicting them standing outside the African House while Hunter herself is shown quietly painting under a tree before them.

The African House Murals are the largest and most celebrated of Clementine Hunter’s creative output. Mignon conceived of the idea as restorations on the building were coming to an end, and he had to convince both Miss Cammie and Clementine that it would be worth doing. With some persuasion he earned their consent, and he then set about making measurements and accessing materials. The work was to be done on several 4’ x 8’ panels, with smaller panels fitting between doors and windows—he proposed to Hunter which themes to explore, suggesting a commemoration of Cane River Country. This suited Hunter, who drew up a model of the panoramic composition, and then set to work translating the rendering into kaleidoscopic color. She worked at the task full-time for six weeks and produced what functions as a composite of her life themes: a work that allows her discordant memories and relationships to flow seamlessly one to the next. Certainly, to stand amidst these paintings is to be immersed in the place-based identity of Clementine Hunter.

View of African House Murals, 1955, oil on wood

All the familiar subjects are here: work in the cotton fields, wash day, a baptism, a funeral, the spring planting alongside a wedding, and ruckus at the honkey tonk. Hunter navigates the large scale of this work by using the lines of the landscape and the flowing undulation of her colors to unite the disparate scenes. Buildings, like open doll’s houses, punctuate the expanse, and dark trees act as visual anchors throughout the composition. The lines of the landscape begin to feel like lines of text, as though the viewer might read the ordered figures and foliage like sentences. These images stand outside of a set time, disavow the rules of perspective, and disregard accurate representation. They are expressions of an inner world—depictions of the landscape of the mind untethered from the restraint of objective realities. To look at them is like looking into a dream, where past experiences coalesce with various emotional phenomena, creating a map of the soul rather than a map of any real place. Consider the circular map of Cane River Country. This aspect of the Murals was insisted on by Mignon, and Hunter obliged without issue; but she found Mignon somewhat resigned with her expression of the map in the end. He had provided her an accurate rendering of the flow of the river and the divisions of fields as a model for her work, but she confidently departed from the confines of the map to render the landscape along terms that resonated with her sensibilities. In the end, her map of Cane River Country became more a map of herself.

Detail of African House Mural, 1955, oil on wood

When visual art veers away from empirical reality, the results can be dismissively regarded as having childlike charm, if they are considered charming at all. Many a museum patron has scoffed at examples of modern art, uttering the now trite, yet persistently derisive, comment, “A child could do that.” In the last hundred years, larger trends in art have explored the aesthetics of simplified and expressive mark-making, qualities associated with the drawings and paintings of children. Hunter’s work can be appreciated along similar terms, but there is something else in her paintings that goes beyond what, by some, might be considered an intentional back-stepping in search of controversy. Picasso is famous for stating, “It took me four years to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to paint like a child.” Suggested in this quote is the challenge faced by adults to rediscover the confidence and freedom they, perhaps, experienced in their childhoods. A child sitting before a blank page, crayon in hand, is understood to be unburdened by perceived expectations of what a “drawing” ought to look like, and, when compared to an adult, is seen as more capable of free and expressive creativity. Adults might reflect on their youth, remembering the last time they drew a picture for pleasure—what stopped them from continuing in their pursuit of this pastime? Clementine Hunter represents a cultural anomaly in that she stepped into the desire to create with childlike tenacity as an adult. Expressing and pursuing the desire to paint was an act of resistance to a culture that had relegated creative expression to the educated elite. The very childlike qualities of her painted scenes fly in the face of the tradition of Western art, snubbing the expectations that the world ought to be depicted in accord with the empirical ideology that underwrites much of Western Imperialism. Hunter painted her truth and, pairing what skill she had with the passion she felt, she brought life to the memories unique to her individuality. The childlike qualities in her paintings express a sense of freedom and self-assuredness, and in so doing, effectively seize what had been withheld from her throughout her life.

Untitled (Good and Bad Angels Flying), ca. 1965, oil on board

The bright colors of Hunter’s work, the affectionate rendering of flowers and foliage, and the seeming absence of emotional pain on the faces of her figures have resulted in her art earning the designation “joyful.” Her compositions may navigate emotionally and psychologically challenging subjects, such as funerals, fights, and hard labor, but her presentation of these subjects is consistently redolent of levity and light. However, describing her work as “joyful” can be problematic, especially if the one making the determination is privileged by our inequitable social system. The adjective “joyful” can be as dismissive as “childlike,” suggesting the artist was somehow blindly ignorant of the complexity of their subject. Worse still, noting the levity of a challenging painting can work to validate an oppressive system in the mind of the oppressor. At no point should the privileged elite allow themselves any consolation when encountering joyful expressions from those oppressed. That Hunter saw the beauty of being alive and chose to share that beauty through her painting in no way endorses the system that kept her bound to servitude and poverty. Rather, the joy expressed by those oppressed must be seen as an act of resistance to the oppressors, a gesture of ardent opposition to the cultural forces that seek to build the supremacy of the few on the backs of the downtrodden many. Their joy must be a rallying cry to the oppressed to never give up fighting for the right to fully self-actualize, to never cease the effort to fully live their life.

Hunter lived to the remarkable age of 101, and passed away on New Year’s Day of 1988. Despite having earned accolades for the artistic work of her later years, she spent the remainder of her life confined to poverty, keeping residence a short distance from Melrose Plantation. Her tiny home was covered in bright wallpaper, decorated with quilts, and had photos and newspaper clippings arranged throughout. In her possession were several noteworthy documents, including letters from three presidents acknowledging the impact of her contributions, as well as the Doctorate in Fine Art she received from Northwestern State University, the very institution that denied her entry to her own solo show in 1955. Hunter’s life, by any measure, could be considered one of success—where her sense of vocation was received and celebrated. Yet she died confined to a life that was determined by racial prejudice—systemic oppression dissuaded her from education, instilled reticence in her with regard to travel, and taught her to expect little more from life beyond hardship. She never complained about the insignificant remuneration she received for her work. She never wanted to leave Cane River County—even when invited by President Carter to visit with him in the White House, she politely declined, suggesting he ought to come visit her instead. Though she miraculously cultivated the confidence to pursue her art, American society succeeded in keeping from her the self worth necessary to grow her horizons and take advantage of new opportunities.

Melrose Quilt, fabric, 1960, 73”x60”

The life and work of Clementine Hunter carries far reaching significance and stands, to this day, as a testament to humble resilience in the face of ceaseless social adversity. The validation of self that was sewn into the soil of Melrose Plantation by Marie Therese Coincoin and her family bloomed into the confident, bold expressivity of Hunter through her paintings. In this way, it is fitting that one of Hunter’s favorite subjects were zinnias: voluminous, vivid flowers of uncountable petals, with a golden ring of tiny blossoms in their center. These flowers, by their effluence of color, assure the world around that it is worthwhile to exist. To paint one’s life is to assert the basic fact that “I exist,” and such a gesture insists upon a social reception. Clementine Hunter’s life can in no way be dismissed, as so many of her peers and ancestors have been, by means of a racist society that seeks to profit through the oppression of others. The translation of her life and home through the murals installed in African House may be one of the more potent symbols we have of America’s true identity: an endlessly varied array of toil, community, religion, violence, and social stratification swirled into a united mass and built upon pain and oppression. Hunter may not have intended this interpretation, but by acting in accord with her sense of self worth, she has set an example that will reverberate for generations to come.

Other creative work related to this article:

Zinnias: the Life of Clementine Hunter, an opera conceived and directed by Robert Wilson, co-written by Jacqueline Woodson

The Sacred and Profane: Voice and Vision in Southern Self-Taught Art, ed. by Carol Crown and Charles Russell

The output of experimental jazz musician, Matana Roberts, who has released four “Chapters” in her 12 part Coin Coin saga. These works explore the complicated and painful history of African American identity, and use the life of Marie Therese Coincoin as touchstone.

Clementine Hunter, American Folk Artist by James L. Wilson

Clementine Hunter

Clementine Hunter is one of the most important self-taught American artists of the 20th century. Her works can be seen in the Smithsonian Institution, The American Folk Art Museum, The Oprah Winfrey Collection in Chicago and countless other museums and private collections.

ChrisTOPHER Clother

Christopher Clother is an artist and illustrator who works primarily with pen and pencil. He received his BA in Fine Art from Portland State University in 2006, and his MFA in Interdisciplinary Arts from Sierra Nevada College in 2019. He is an art professor at College of the Siskiyous in Weed, California.